The Alcazar to Al-Andalus

In the gardens of Sevilla’s Royal Alcazar, Moorish influence in art, design, and architecture transports us back to the time of Al-Andalus

Over 500 years have passed since the last Moorish forces were exiled from Spain, and Al-Andalus was no more. The closing of one chapter and the opening of the next bore into existence a new player on the global stage—one in which the influence of Moorish food, language, art, design, architecture, and culture were palpable strands in the fabric of society.

Today, the spirit of Al-Andalus still pulses through Spain. It is a living force to be experienced by all human senses—tasted in the saffron of paella, smelled in orange blossom tree orchards, heard in the soulful “ay-ay-ay” transitions of flamenco music, and touched in the pools of hammam baths. It is with our eyes, however, that we witness the most striking and emblematic Moorish relics. The fortresses, palaces, and mosques that once served as their strongholds are now treasured Spanish landmarks.

It is the permanency of Moorish legacy manifested in the stucco-covered buildings, horseshoe arches, geometric tiles, and ornate designs that people travel from all over the world to see. Nowhere can this be more effortlessly observed than in Andalusia, the southernmost region of Spain and the former capital of Al-Andalus. Here, in a fortress built for Caliphs, we arrive at a portal to Spain’s Moorish past, The Royal Alcazar of Sevilla.

A Gateway to Spain’s Moorish Past

Under a dim morning sun, I move briskly through the streets of Seville in a daze. The city is just beginning to stir. Cafe and shop owners prepare for a day of serving patrons as they haul tables and chairs outside and set up stands full of souvenirs. I identify another nearby sound as horse hooves clomping through the streets and pulling one of the city’s signature marigold-painted carriages behind them. The rhythmic beating of their steps adds a tranquil soundtrack to the crisp, still-quiet morning air.

Though my senses are pulling me in all directions, and my curiosity beckons me to explore every inch on this walk through the cobblestone streets, I am determined to arrive at my destination. I glide past the Gothic cathedral and Giralda bell tower, beloved Catholic and Muslim constructions that sit side by side and ascend hundreds of feet into the sky. This has to be it, I think, as I turn my attention from one architectural wonder to another: The Alcazar.

I run my eyes down the towering walls of human-sized stones to a tightly packed queue of visitors, confirming my suspicions. I am as eager to be here as I am grateful to have arrived so early. Taking my place in line, I begin to digest my first glimpse of the Alcazar—or at least the outer masonry. The Moorish builders topped these defensive walls with sharp, pointed battlements, permanently readying the fortress for an attack.

Today, far removed in time from medieval armies, these walls are regularly breached by photo-snapping tourists. I contemplate this irony as I am shepherded towards the entryway—Lion’s Gate, as it is appropriately named. The red clay-colored entrance is adorned with a cross-wielding and crown-totting lion that sits above an oval-shaped opening in the wall. The Gothic design and banner etched with Latin writing feel out of place, but such is an artifact that has passed between kings, languages, and empires.

Inching through the large courtyard just beyond Lion’s Gate, I officially cross into the perimeter of the Alcazar. There are three potential routes in front of me, all uniquely enticing as if prompting me to make my first selection in this choose-your-own-adventure game. I do a quick survey of my surroundings. To my right is a door that sits behind tall lobbed arches and leads to a dark room. Directly in front of me, I’m invited into the official royal palace by a towering, ornate facade of intricate carvings and designs. However, it is the more subtle horseshoe archway to my left whose gravitational force pulls me in.

Before I know it, I’m headed down an unassuming pathway that the map in my hands says will ultimately lead to the gardens. Butterflies are rising in my stomach. A twinge of hope and adventure, as if I am passing through the wardrobe doors to Narnia. I’m tempted to soothe my excitement, but instead of letting adulthood rationality squander child-like wonder, I revel in it. I allow my joy and curiosity to bloom unhindered. A kind of ritual to prepare for the magic and mysticism that are to come.

Gardens of Paradise

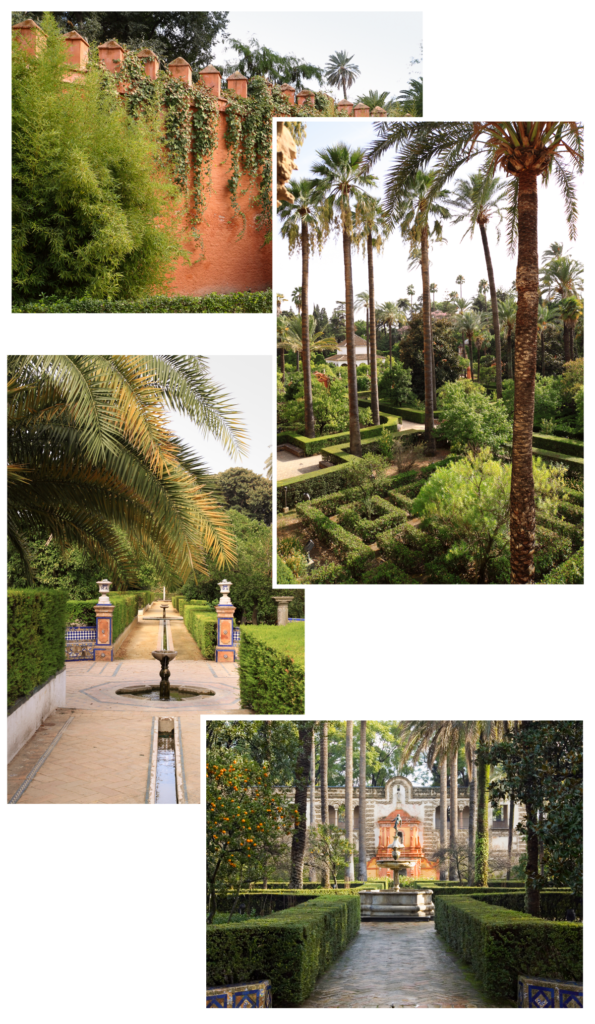

Stepping onto the balcony above the grounds, the famous gardens of the Alcazar burst into view. They are a vast labyrinth, a wonderland of connected pathways dripping in Mudejar and Renaissance motifs. To my left, the Grottos Gallery uses an original Almohad wall as a canvas to display its grandeur and provide an illustrious backdrop for a bronze statue of Mercury. These Western European additions were introduced as succeeding Catholic kings came to favor Italian design, but they do not overshadow the Mudejar essence of the gardens. As is typical with Islamic art, designers forgo the use of personifiable subjects and opt for geometric, vegetal, calligraphic, and architectural elements to deliver their messages. At the core of their work is a consideration for the divine.

Here in the Alcazar, the gardens are a sixty thousand square meter metaphor, born to symbolize heaven on earth. The oasis mimics the paradise promised in the writings of the Quran and provides a blissful space for peace and quiet reflection. A paradise indeed, with its assortment of tall, tropical trees whose shade offers coves of solitude and a direct connection to the natural world.

Architectural Marvels in the Alcazar

I continue through this Eden, savoring the taste of exploration without a destination. Above, birds fly between trees and past the pavilion of Carlos V, a square-shaped building erected in honor of the king’s marriage to Isabella of Portugal. Nearing the structure, I am reminded of what I find most impressive about the Moorish legacy in Spain: that despite the robust efforts of the Reconquista to reclaim lands and control of the peninsula, the rulers that followed not only preserved elements of the Moorish presence but enthusiastically integrated them.

This pavilion, dedicated to a royal Catholic marriage, has its roots in a Muslim Qubba and seamlessly merges Renaissance-era columns with Mudejar glazed tiles. Inside sits a sole fountain, level with the ground and walled by geometric forms and twining, foliated patterns. The domed coffered ceiling offers a display of one of the most brilliant and sophisticated features of Mudejar architecture—one that is repeated, each time in a unique form, throughout the Alcazar.

Hedged bushes line the walkways and accompany me as I wander deeper into the gardens and lose my place on the map. I’m tempted to spend the entirety of my day getting lost in this botanical maze, enjoying the company of friendly peacocks, and scribbling notes about things I don’t want to forget—the last of those being about the exquisite fountains found at the intersections of pathways. Sitting close to the ground, if not on it, the fountains contrast the monumental and grandiose style of others in Europe, and provide a more spiritual and meditative purpose to all who are pulled into their orbit.

The water fountains and narrow channels that run between them are said to allude to the abundance and purity of God’s promised paradise. They are picturesque representations of Mudejar design, enclosed by painted octagons, hexagons, and other geometric shapes. Delicate Arabesque blue, yellow, and green tiles add dynamism to the two-dimensional composition and create complexity by repeating simple designs. In the balanced lines and spirals that adorn the fountains, there is a sense of both tranquility and structure—a mesmerizing scene from which it is difficult to tear your gaze. It is no wonder that the gardens and their dreamy fountains were muses of inspiration for the likes of Joaquín Sorolla and the producers of Game of Thrones.

Discovering the Enigmatic Depths of the Alcazar

In a slightly hidden part of the gardens, I descend a short flight of stairs and enter the baths of Lady Maria de Padilla—a space initially used as a water cistern in the 12th century and then as a bathing spot by the mistress of King Peter the Cruel.

The air is cool and quiet, and my vision attempts to adjust to the dim underground chamber. My attention is quickly drawn to the ceiling where Gothic ribbed vaults zig-zag my focus left and right until arriving at a long, narrow pool that extends the remaining length of the corridor. For a moment, I question whether I see one repeated image of the arches in the water’s reflection. On the yellow-hued walls, natural light spills in to cast deep, contrasting shadows. There is an illusionary and almost haunting energy here, where silence and soft echoes bring you to a dreamlike state. I don’t know whether it is the optical illusion effect of the water or the gentle lighting soothing me into a trance, but I discard my notepad and pen into the bottom of my tote bag and heed a call from my intuition to just be.

The child-like wonder I felt upon entering the Alcazar is still there. But in my solitude, I come to feel its true ethereal nature. Through empires and over a thousand years of change, the Alcazar has remained—a time machine that has been altered and transformed to reflect its surroundings. Through the wardrobe doors to this Narnia, there were no lions, witches, or magical creatures, but enchanting labyrinths to wander through and footprints of past souls to follow. I ask myself if those who walked the grounds of the Alcazar all those years ago experienced the same otherworldly spirit that I feel at this moment or if it was, perhaps, left here by them.

A version of this article appears in print, in Issue 1 of Álula Magazine with the headline: “The Alcazar to Al-Andalus. In the gardens of Seville’s Royal Alcazar, as if transported back in time to Al-Andalus, Moorish influence lingers through its art, design, and architecture”